The parallel between the personal tragedy of an individual and the collective tragedy of a people is clear in TAHA play. It is a gripping show, a one-actor monologue that made the audience weep in sorrow, empathy and compassion. Numerous, and great, articles and reviews have been written about the show, especially since it was translated and performed in English abroad, but what I want to do is to write about my experience watching that show in Haifa- the bride of the sea.

Beit El Karma is an Arab-Jewish center skirting Wadi-Nisnas neighborhood in Haifa. The center opened its doors upon a last minute request from the organizers to have Taha’s show there, due to the rainy and cold weather. At 8pm, the hall was almost full and everyone was waiting for the star of the night Aamer Hlehel- a Palestinian actor, director and performer. He comes originally from Qaditta that was displaced and destroyed upon the establishment of the state of Israel, but he is based in Haifa now.

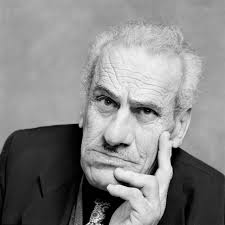

(Aamer Hlehel as Taha. Photo courtesy: The Independent)

“انا أجيت غصبًا عن الدنيا” “I have come to this life in spite of its will”

The play begins with an announcement, a declaration of some sort that Taha’s mere existence has been a defiance, for life didn’t want him to come but he did, anyways. He tells the story of his birth- his mom gave birth to three babies only to die before seeing three moons, and then Taha arrived. His arrival to this world has been a struggle, his life as struggle, and his poetry a triumph.

Weaving the story of Taha’s childhood in Saffuriya- a small village next to Nazareth, the writer deftly shows the reality of the Palestinians before the Zionist state was established. The story of the family’s displacement to Lebanon, of living in utter poverty in a country that is not theirs is intertwined with the personal story of Taha’s relationship with his dad, who represents the values of patriotism, family, responsibility and holding on to the land. The interconnections between the personal and the national, the change of outer, spatial elements and inner dynamics of the family and of Taha’s self produce a strong feeling: a feeling of identification of Taha as a person, and Taha as a Palestinian case. A zoom in and a zoom out that leaves one only to solidify the feelings of tragedy, intifada and attempt to defy- not to surrender, never.

Haifa

Haifa has a special place in people’s hearts; in Palestine’s heart. The play presents the poet’s first encounter with Haifa before 1948, when it was under the British Mandate. His first visit to the bride of the sea where he saw bustling life, heard different tongues, smelled the sea and climbed its hills. He is amazed and mesmerized by Haifa, and describing it in front of the audience, that is mostly from Haifa or has lived in Haifa after the destruction of many surrounding villages, one can only point to, but never capture, the high degree of emotions that is involved in such a memory. Haifa- the city we have lost, the city we live, the city of contradictions, and the city of grace. Being in the physical place and listening to the mental, emotional captions aids the audience to watch this “chasm of memory” (as Hussien El-Barghouthi calls it) that no one else sees and feels, and from where a geyser of power rises.

Chronologically moving in time and space, Taha escapes Lebanon and returns to Palestine, only to live in Nazareth and not in Saffuriya- his hometown. The horizon overlooks his hometown- so far and so near, but he cannot go back to his home, to his olive groves, nor to his days of seeing Ameerah (his cousin and love of his life). How painful it is to be deprived of your home that you share many memories with, only to see some new Jewish immigrants coming from Poland to live there? but can they see what he sees? Do they have access to the “chasm of memory”? I doubt.

Out of pain, poetry rises like a phoenix as the remedy. Taha declares to himself: “سيكون الشعر ملاذي في الحياة / poetry will be my refuge in life”. The philosophy of his life becomes “writing everyday”. Reading and devouring books, teaching himself English feed his desire to write. And he writes. He writes poetry:

His poetry is different from the revolutionary, inflammatory poetry of Tawfeeq Ziad or Sameeh El-Qasem, who were well-known poets at his time. What I like about it is its tranquility- one can notice the amount of thought, meditation and pondering that built such simple lines, sophisticated images and capturing emotions. It is as if each word- written with ink or printed on the digital screen has a dimension that measures the amount of contemplation that produced it, and for his poetry i feel this dimension so deep. As his poetry is inspired from personal experiences, it is recited in the play at different stages of his life.

The audience varied in its age-range, but almost all the Nakba’s second-generation were crying and even sobbing. The fact of containing the sadness of losing your home, your country, your lover, your family and still have this passion for life and for reading is surpassing all other feelings of defying life.

He ends the play with the same quote- that he came to this life against its will, and he fought by his existence, and he wrote his existential resistance on paper.

Rest in Peace, Taha Muhammed Ali.